The Fisherman had died. This came as a bolt out of the blue, while I was still in the UK preparing for my return to Martinique at the end of the summer of 2019. He was almost the first person I’d met when I’d first arrived on the island, what seemed like a mini-lifetime ago. He’d been sometime crew of Anne Bonny, boyfriend to my First Mate Mary Read, and source of so much nature-wisdom. He was half man, half sea creature, and had repeatedly promised to teach me how to spearfish, though I never organised myself to take him up on it. I’d always thought we had more time. In those days he’d moved out of his mother’s house and was living in a fisherman’s cabane along the beach at Ste Luce. He was in a crowd of older fisherman, who were looking after him and the small brood of chickens he’d lovingly built a stilt-hut for. We don’t really know for sure what happened to him, but Mary told me he’d gone out fishing one day and his partner in the boat had not been a confident diver or swimmer. I could hear the frustration in her voice as she’d explained this. He had always been so strict with safety when it came to other people, but hadn’t wanted to ask his friends for help on this occasion. He’d also been pushing himself to dive deeper and stay down longer. He’d even bought a special watch. She thinks he’d blacked out and his partner hadn’t known what to do, or hadn’t been able to find him from the boat. Hurricane Dorian (or was it just a tropical storm by then?) was due to hit the next day, and nobody had been able to go out and look for him. It was a horrible time, because Mary was sure he was dead, but his family were so full of hope. They thought they’d find him alive, miraculously, somewhere. I don’t want to speak for Mary’s feelings, but she seemed as angry with him as she was upset. It was a relief when, a couple of days after the storm, his body washed up on a beach. He was 22.

The 2019 return to Martinique was a weird time, overshadowed by the death of the Fisherman, and later another friend. Friends in the tropics are often seasonal, and the gang of Sainte Losers we’d formed had mostly disappeared with the summer cyclone season. Rachel and Mme Ching had gone back to their ‘real lives’, The Poet had vanished into the jungle in Guyane, waxing lyrical about the creative wonder of the dichotomy of shamans and space exploration. Grace had gone to France to start her Masters, and most of the Language Assistants we’d befriended that year had finished their contracts. Of the Sainte Losers, Labrador Eyebrows and a couple of other guys who lived in the squat remained. I always thought of the Sainte Losers as Lost Boys (though not all of them were boys) – living in this in-between state of partying and never really growing up, working in restaurants and on boats to fund their adventures in the tropics, the ones from the squat being drawn further into Neverland. I don’t want to claim to be Peter Pan, but I felt like one of them, and I wasn’t ready to give that life up either. Maybe I was Tinkerbell.

I also had a gang of non-seasonal grown-up land friends who never showed up in this story because they didn’t get involved with Anne Bonny, but they were my besties. (What are you doing right now? Nothing? Come round for breakfast on the terrace. And by breakfast I mean beers and cigarettes.) The relationships you make in a transitory lifestyle are complicated. You can have lots of little intense fleeting acquaintances which are enjoyable at the time, but never become lasting friendships. Some people limit themselves to these surface relationships because the alternative – finding friendships that satisfying your emotional craving for more depth, more connection – can be wrenching when you say goodbye again and again. And the people you say goodbye to don’t find it any easier. There are certain of my Martinique friends who I fully emotionally invested myself in, and not having them in my life any more is so sad.

Annie B and I went out sailing a couple of times, with some moonlighting cabin boys and a few other pals. But I now had a very clear project: sell her as quickly as possible. I went through the paperwork tedium of paying import tax and re-registering her in France, to make her a more appealing prospect for a local buyer. (I cannot overstate what an absolute administrative misery this was, but I’m pro at French/Caribbean bureaucracy at this point.)

To give me some focus while I was trying to sell her, I started my new job as Charter Boat Cook and my eyes were opened to a new world. We did a speedy budget package from Martinique to Bequia, to the Tobago Cays, Union Island, St Lucia, and back to Martinique, all in one week. The groups were all French and without exception made some kind of joke to the tune of ‘oooooooo an English girl is going to cook for French people?! Do the English even know what food is? Hahahaha’ (I used to time them to see how long it would take them to comment, and once it was before they had even boarded.) I refrained from joking back that if they let me cook, I’d agree to listen to French music. Anyway, it was exhausting and I was often seasick, but I genuinely loved the job. The budget provisions were crap, but that just meant the guests were extra complimentary when I managed to make something they considered edible. And when the guests annoyed me too much, I just stopped being able to speak French. For some reason I got away with being openly rude to them in English – they found my accent charming and thought I was joking.

What I hated about the job was the constant disrespect from the ego-driven skippers I worked with. There was a definite sense that your female cook was mostly there to look attractive, and was not considered a real sailor. So many of these men lorded about, arrogant, bragging, only treating other skippers as worth talking to. Really, as a female ‘hôtesse’ (the men doing the job were called ‘cooks’) I felt like the universe had slipped back into the 1950s. There were a few awesome skippers of course, and this definitely wasn’t the rule, but the one time I felt like we were working as a genuine team was the time I got to partner with the Ultimate Unicorn. Her name was Auriane, and our guests waited patiently after we had introduced ourselves to them, for the real captain to show up. She was my age, she was charming, she was attractive (which was usually the only descriptor people used about her) and she was Martiniquaise (so she also had racism, which is present in sailing too, to contend with). It took her a while to win the respect of our passengers (and I know she had a lot more difficulty with some other slightly more misogynistic groups), but we had the best time working together. I’d never had any ambition to work seriously in the maritime industry, let alone become a professional Skipper, but it was the treatment I received at the hands of all this disrespect and generalised misogyny which made me think ‘shit, we need more women doing this if the atmosphere is ever going to improve’. My stubborn attitude told me I had to become one of those women.

The season wore on. I sold the boat (yay! One of the 2 best days etc – plus I won the game because I sold her for more than I paid), and moved back into my original home in Ste Luce. Flav went to live with Labrador Eyebrows, much to the disgust of his squat-mates. For some utterly incomprehensible reason, they found him creepy. Apparently he wasn’t happy there. I tried to encourage dressing him up in costumes, order to lift his spirits as he looked out over the neighbourhood from L.E.’s balcony, but perhaps after all he had preferred his life at sea. They broke the news to me later that he had se suicidé, and to say I was devastated would be an understatement.

I got dengue fever for Christmas (you can’t spend 4 years in the Caribbean without participating in a local tropical disease epidemic), and danced in the New Year with sobriety (and mainly Big Fish Little Fish Cardboard Box) at a beach rave, which I decided was the only way to do New Year, from now on. Then came Carnival, and we’d started to hear mutterings of islands turning away boats from certain nationalities – like Italians. Apparently Europe was worried about a new Chinese disease and were bringing their neurosis to our shores. Everything in Europe always seemed so far away and a bit irrelevant. We didn’t take it that seriously.

Halfway through Carnival, we all had to say goodbye to Labrador Eyebrows. His time as a Lost Boy had come to an end. I’d seen him morph from a 21-year-old fresh and charming Will Turner to a sea-worn bearded Jack Sparrow. He was still my favourite, though. Our friend Robin, a returning Sainte Loser visiting for Carnival, explained what I didn’t realise I was going to feel. He said he’d once spent a year in New Zealand, and it was the best of times (the worst of times?). It was such an incredible period in his life, that he can’t even reminisce about it, because thinking about it and knowing he’s not in that moment any more is too painful. He hasn’t been able to replicate that feeling anywhere else, and for him it’s agony. That’s Martinique for me. We partied like it was the end of the world, and with Covid on the horizon we didn’t realise it was.

The day after I arrived back from the latest charter, the government announced confinement, and a whole new set of rules that were to govern our lives. Like everywhere else, we discovered the concept of Tiktok, and the obsession with washing our hands for 20 seconds. Except for us there was a drought and most people’s houses had their water cut off for days at a time. We looked at the skies and prayed for rain. In the meantime, Head Office called me up and asked if I would go on a rescue mission to the Grenadines to repatriate some of the guests. Of course I would! I was still knackered after my charter (and frankly, looking forward to being locked in my room indefinitely) but I can never say no to adventure. Turns out I wasn’t strictly allowed to leave the house to go on this quest, so a certain amount of sneaking was required. Myself and one of the chief skippers picked up and big catamaran with some hastily cobbled-together provisions and sailed away when we knew everyone else was being locked down. It was really chilled and enjoyable, and slightly rebellious-feeling. I tried to think of some tasty meals to make out of the assortment, as the brief was ‘still treat them like they’re on holiday’. To be honest, they were not best pleased at being rescued, complaining loudly about the shortening of their trip. We had to present them with hand sanitiser and keep them at a distance (no-one was yet sure what sanitary rules we were meant to follow), which they thought was all overkill and ridiculous. They didn’t see Europe’s problems as ours either. But the other islands were closing their borders, and these guys needed to get on the last flights home.

When we arrived back in Martinique, the skipper and I were ordered to abandon the passengers on the boat and run away. The passengers, with the few provisions they hadn’t eaten, were now supposed to fend for themselves until a flight could be organised. No, they weren’t allowed to leave the boat. 12 of them, all imprisoned together. They weren’t happy bunnies.

I luxuriated in the novelty of this weird situation, joining in with a bit of the ‘don’t touch anything or let anyone breathe on you’ paranoia, but mostly looking forward to my daily beach walks, and working on this writing project. Like many, I was looking forward to having the time to do all the things I didn’t normally have time for, and getting stuck into the plethora of free entertainment that became available. My group of friends back in Scotland got together in memory of our friend who had died (the catalyst for my buying a boat in the first place) and invented a really inappropriately-titled game, ‘Chinese Face’. He’d come up with the concept by accident in a taxi one day – ‘wouldn’t it be cool if there was a game where you try and copy someone else’s face, and the next person tries to copy yours, and then the next person. Like Chinese Whispers. It would be, like… Chinese Face!’ At the time we’d just rolled around laughing because the name was so culturally inappropriate. ‘You can’t call it that!’ So we all came together on a group chat and played Chinese Face, by taking a selfie pulling a face, and then passing it on. It was surprisingly fun and brought us all together in a really comforting way, in all our different time-zones. I loved that bonding moment.

After a month I was starting to get restless, though. I heard of some people leaving on a Transatlantic, and though I hadn’t really planned to get back to Europe that way, it appealed to my sense of adventure. I wasn’t really looking, but I saw a Facebook post by someone looking for crew from Guadeloupe, and to be honest the guy in the profile picture looked really hot, so why not? We started making plans for me to join, and I was all set to tell my fellow inmates that I had to leave, when he suddenly announced he’d found other crew. It had seemed almost impossible to get me to Guadeloupe from Martinique anyway, and these guys were on the boat next door to his, so what could he do? It was a pity because the job was pretty well paid, but now my mind had opened to the idea of doing the crossing, so I put feelers out among the boaty community in Marin.

Soon my colleague Fred got in touch saying he needed a last-minute 1st Mate, that he would pay me, would I be ready to leave in 3 days? I scrambled to make it possible. We needed other crew so I asked Boat Guy, but when I told him the boat was a Lagoon 42 he replied ‘actually nah, not in a Lagoon 42’ and preferred to stay confined to his bedroom. We had resolved to do the trip double-handed (for better or worse), when two of our charter company colleagues stepped forward, keen to get back to their kids in France. I was able to pass by the squat on my legal daily walk to say goodbye to the boys through the gate, and a friend came by to pick up some things I was leaving behind on the island; but aside from that I had to leave without saying goodbye any of my friends. I didn’t know if I’d see any of them ever again. Without a boat or a job here, who knew if I would be coming back?

We met at Fred’s company catamaran, officially to ‘help him clean up and move out’, but really to have an illegal lunch. After the claustrophobic confinement atmosphere in town, life in the marina was another world. We’d scuttled up to the boat, hoping no-one from Head Office (I’ll not name the company) would spot us as we were all breaking contract by leaving – and they knew Fred had a Transat booked. But once we were there, everyone was relaxed. We dug through the leftover charter supplies, working out what we could take away with us, and next door invited us over to cook some of it up and share lunch/too much booze. Most of the charter catamarans were occupied by discombobulated crews (normally a Skipper alone, or Skipper + female partner combo) who had either missed their chance of a rescue flight home, or were bound by contract to stay and were just waiting it out at the company’s expense. I was a little jealous, if I’m honest. Here they seemed to have a much greater sense of space and freedom. It would have been a totally different story if I’d still been aboard Anne Bonny in my cramped marina in Trois Ilets. And for those at anchor I hear it got pretty bad sometimes, with police roaming the anchorage trying to enforce confinement rules on a group of people they seemed to regard as dangerous rebels. During that time, we got the impression the authorities really didn’t like cruisers, and I think a lot had to do with a sort of resentment, jealousy or just plain judgemental attitude against non-standard lifestyles. France loves conformity.

Lunch on the abandoned charter catamaran gave me a bizarre sense of joy in the industry I found myself in – the mad on-the-edge people you found working in it. I was really excited to have the sort of colleagues I could disappear off on an adventure with.

We set about stripping Fred’s boat of anything we thought we’d enjoy eating or drinking on the crossing. We had boxes of rum, wine, remaining beers from whatever the last trip had been (farewell to the idea of being a ‘dry’ boat). I was envious of all the provisions they were given on these boats – Fred worked on the deluxe charter. I was used to purely economy class. We decided against the 4 tubs of ice cream, but kept a good deal of meat and tinned veggies. There were cheeses (the mascarpone would bring us joy later on), olives, snacks. All sorts of yummy things. We took note of it all to compare with the hefty provisioning plan I’d made, and loaded up the dinghy for Fred to smuggle over to the other boat after dark. At one point Head Office boss came by and I had to hide. She was very chill about breaking confinement rules, but as we’d already lost a crew member to her lack of chill about contract breaking, we didn’t want to take the risk. Everything we did felt illegal, and therefore very exciting at a time when the expectation was sitting in bed watching Tiger King (I managed one episode) and using some thing called Zoom (never tried it until late 2022) to do ‘parties’ with friends.

The Big Shop was a mission. At this point we were still only moving about grace à some bit of paper signed on your honour (trust the French to use the pandemic to create more bureaucracy). I had hand-written a bunch out and was subtly altering the date and time so I could reuse them. We all had bits of paper proving we were working with Fred, to try and legitimise our illicit movements. Filou and Laure picked me up from outside the house at Ste Luce, me mostly packed and ready to move out. Fred had sourced some sanding masks and engine oil gloves for us, which was the closest we could get to PPE in those days. The big supermarket was a 20-30 minute drive away, and officially we only had 1 hour liberty per day. They were also controlling the amount people bought to try and prevent panic buying and hoarding. Excited and struggling with the masks, Laure and I grabbed a trolly each, and the separate lists I had made for each of us. My tactic (in case they stopped us buying too much of the same thing because of the panic buying) was to divide the quantities between two, but not the content of the list. So for example, my list would read ‘2 brie’ and so would Laure’s. I don’t think I managed to communicate this fully to my colleague. She seemed to have looked at my list and thought ‘2 brie? That doesn’t seem like enough. I shall get 6’. So our shopping seemed enormous and Fred had kittens when he had to authorise the bill over the phone. At the end of the day, Laure’s abuse of the budget led to a very fattening but enjoyable trip, but may have contributed to the reason why I didn’t really get paid as promised.

The shopping took hours, and halfway through we were starving. Laure grabbed a couple of sandwiches from a shelf and ripped them open. She handed me one with a gloved hand, and I’d taken one bite (‘bon appetit’ said the fellow shoppers) when I realised that her gloves had been touching all the ‘Covid-infected’ produce. This was why we were wearing gloves!! She took the sandwich away from me, replaced it on the shelf, and opened another one without gloves. We were so paranoid in those days. I’d never eaten a sandwich in the middle of the supermarket before.

We were stopped at a checkpoint on the way back to the boat, hearts beating fast because the car was filled with excessive groceries and having used up our allocated ‘freedom time’ for the day. We tried to run through excuses or ways to cheat the system. But this is the Caribbean, and we were women. The Gendarme didn’t even bother to look at the form. Back at the boat, Fred and Filou were doing Technical Man’s Things to prepare the boat, so we prepared a sink full of soapy water and proceeded to wash and dry everything we had bought. This proved to be quite bad for long-term storage and we had a mould problem later. It was also really time-consuming and as darkness fell, we realised – shit, there’s a curfew and I still had to move aboard that night. Fred still had stuff to retrieve from the other marina so he disappeared off in the dinghy; Filou and Laure drove me home to pick up my bags and do a last clean of my room. Plus say a teary final farewell to my confinement inmates, who weren’t expecting me to just suddenly take off.

We had 10 mins before curfew and we still weren’t back at the boat. Plus Filou and Laure still had to get back to their apartment. When we arrived at the marina, it was all locked up and Fred wasn’t around to help. We had to fling my bags over the fence and break in. That evening, Fred and I shared dinner and a glass of wine, and came up with a vague plan for running the crossing because tomorrow bright and early (with Filou and Laure boarded), we were leaving.

Even leaving Martinique, we felt like fugitives on the run. As we started to make distance between ourselves and the Marin channel, the coastguard followed us in their helicopter. Where are you going? They demanded. You’re breaking confinement. Yachting is forbidden. Fred told them we had no choice, we were obliged to return the catamaran to Europe before hurricane season, and then stopped responding to them. They left us alone after a while. I can’t even remember if we’d checked out officially. We felt the thrill of the risk – but every time someone coughed there was a shadow of dread. The other professional crews, doing deliveries for commercial companies, had been obliged to spend 2 weeks isolated at anchor before setting out for the Atlantic. Fred didn’t feel this was necessary. He trusted all of us to have been following the rules correctly… there was no chance any of us was already ill, surely? All the same, we spent the first week of the trip feeling a tiny bit paranoid, before forgetting there was a pandemic at all.

As we passed wide of Dominica, we heard another yacht call for help from the French coastguard, claiming they were being boarded by Dominican authorities and having money demanded of them for passing too close to the island. The speaker on the radio was sounding more and more freaked out. ‘They have guns!’ He pleaded. ‘Help!’ Dominican coastguard had never asked for money from passing pleasure vessels before, let alone boarded with guns. This felt like it was becoming the wild west. We eavesdropped with baited breath as a helicopter was sent out from Guadeloupe to intervene. We were glad to be getting out of all this mess.

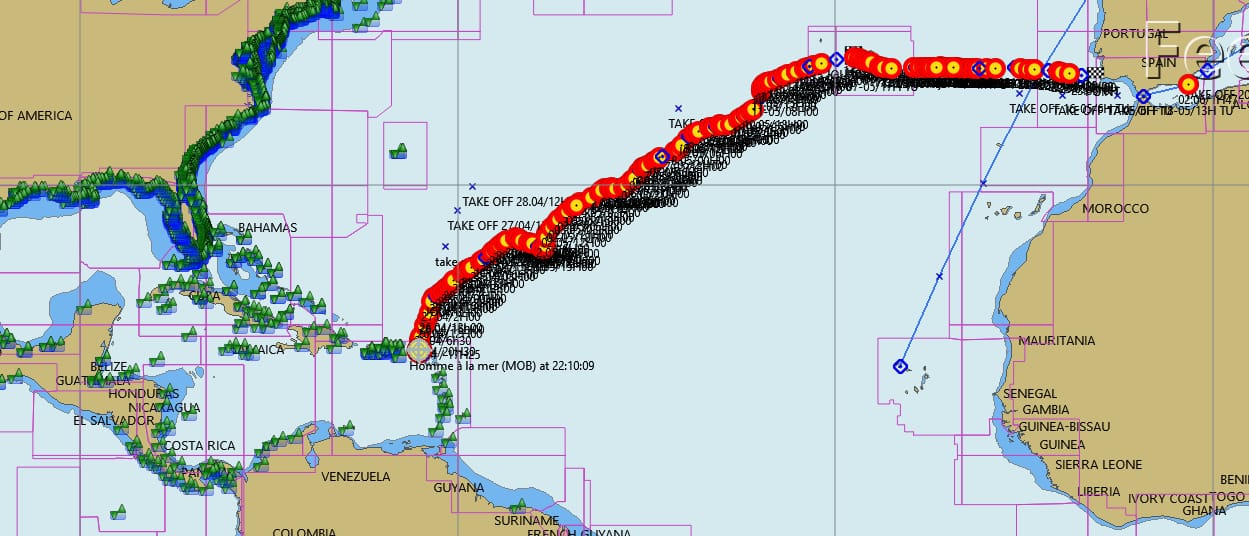

We anchored in Deshaies and found my failed superyacht ride was there too – so in the end I did get to meet the hot guy from the Facebook ad. We kept up with them on the AIS for a little while (I’m not going to say ‘raced’ because we were way outgunned) until they disappeared off the screen to make it to Spain in 23 days, they told us. Then we refuelled in St Martin, before taking a deep breath and heading out to sea proper.

This Transat was different from my last in every possible way, not least because I spoke French and was a professional seafarer now. Plus, we all liked each other. Every day we dug through the appros and said Grace before each meal ‘For what we are about to receive… thank you Head Office for this bounty you have provided’, drank good wine, followed by good cheese, and played cards together. We lounged about in the day reading books or watching films, watching the sargassum drift by, and later the Portuguese Man o War. We caught some fabulous fish, we discussed too much politics (never discuss religion or politics or feminism on an ocean crossing), we even sang songs. We swam in the middle of the deepest blue ocean. We forgot this fresh new pandemic hell that everyone was enjoying.

But the good times didn’t last – of course they didn’t. Because this boat was a Lagoon 42, and there had been more than one person who had warned it wasn’t the best-built machine. A friend had given me a list of all the things he thought would go wrong, and slowly but surely he was proved right. The biggest of these issues was the autopilot, which leaked all its hydraulic fluid away and, as it turned out, we didn’t have any spare. I hand-steered whilst frantic discussions happened in French, and the guys tried to collect as much of the drained-out oil as possible. One of them had mentioned that Eric Tabarly (or someone, maybe it was Moitissier. One of the French legends) had heated the oil/water mixture and evaporated off the water. Or had just used olive oil. Anyway, the hydraulic oil sat there and bubbled on the stove in a vain attempt to purify it. The autopilot actually continued to work for half a day or so after this chemistry experiment. Then it didn’t, and we found ourselves hand-steering. Fred’s decision is one that none of us agreed with – which was rotations of 1 hour on/3 hours off. For some reason, he thought we could only manage hand-steering for 1 hour at a time. This was a catastrophic tactic. In those 3 hours, nobody slept, and chronic sleep-deprivation very quickly became the name of the game. By day 6 without autopilot we were at each other’s throats, and by day 8 no longer really on speaking terms. Thank fuck for the sighting of the motor yacht on the AIS. Filou called them up, and told them our situation. Was there any chance that they had some hydraulic oil we could borrow? By the time he managed to communicate with them, the boat was already on the horizon and we thought the chances of them turning around for us were slim. But then the miracle: they did, and what was more, they sent a whole barrel floating over to us. We fished it out of the Atlantic like it was lost treasure. What it represented was liquid sleep.

We’d thought the whole barrel was slightly overkill, but since the autopilot continued to steadily leak the oil away, it was lucky they’d sent so much. It was just enough to get us back to Europe, with daily checks and top-ups for the rest of the voyage.

We couldn’t see Faial as we motored up to it on our last gasp of diesel vapour, but we could smell it. And we knew she was there in the mist somewhere from the sudden pinging over everyone’s mobile phones. That magic thing – phone signal – is both an extreme joy of a long sea voyage, and a bit of a disappointment. Now we’d have our first glimpse of what chaos had been going on in the real world since we’d set off 3 weeks ago. We were hailed on the radio as we entered the bay of Horta. We could anchor, but we wouldn’t be allowed ashore. We would need to organise a visit from Customs and Immigration the next morning. It was close to sunset, and we could see our charterland colleagues on boats already anchored, with a few arriving behind us. A dinghy sped towards us, with grinning faces barely discernible behind full-face breathing masks and hazmat suits. The young guys waved cheerily, and shouted an enthusiastic welcome. This is when we realised everything was going to be OK. Honestly, the amount of effort the people of the Azores went to make the crossing boats welcome made such a difference to that over-long passage.

This was the team from the infamous Peter Café Sport, it turned out, and they were here to get us anything we wanted. We wanted cigarettes and information. They zoomed away and very quickly brought back cigarettes and told us the lowdown about what we were to expect in Horta. It was so good to see humans. We arranged a trip to the fuel dock the next day, and the possibility of real takeaway pizza (they flourished all sorts of menus from the local businesses). Customs and Immigration were equally kind and enthusiastic to see us. They really made everything as easy for us as they could. At the fuel dock, we were able to totter about on the solid pier (but no further), admiring a performance trimaran that had been punctured by an enormous moonfish mid-crossing and had been granted an extension to the 2-day stay limit to do their repairs. We checked out the famous murals left by all the other passing boats. We outed the mascarpone and created a spectacular Terre-i-miss-u to go with the pizza which a local restaurant had kindly made for us. Our order had been ‘surprise me’ and they’d sent huge slabs covered in what looked like their entire menu. Peter Café Sport took a grocery order and brought us a whole load of fresh goodies to continue along with.

The Transat already makes you feel like edge-of-reality explorers, but this year particularly I think we all shared a sense of being pioneering outlaws. To see others embarking on the same project (when so many people opted not to take the risk of possible Covid en route, or being perpetually at sea and facing closed borders on the other side) gave a sense of camaraderie like no other. Friendly as the Azores’ welcome was, they kicked us out fairly sharpish and after a visit from a hazmat-clad engineer to look at our autopilot, we took off out to sea again. (Incidentally, that problem plagued us the whole way, but we never had the 1 hour on/3 hours off torture again.)

The ocean can do weird things to your mind, which can be intriguing, if emotionally challenging. The sensory deprivation of moving in what feels like wide disc towards an eternally empty horizon gave me extraordinarily vivid dreams. While I was awake and left with my own thoughts, my brain decided to use the opportunity to get out and dust off everything I used to hate about myself and thought I had moved on from or forgotten. I spent a while feeling pretty depressed, and there was no escaping it. It’s a dangerous state to sink into, because it affects everyone else on board. I think I only indulged my moods for a couple of days before pulling myself out of it. No ocean sailor can help becoming a philosopher. Luckily we also danced together, chatted, played games, watched movies, and admired the incredible sunsets (the best green flash I’ve ever seen).

You know you’re arriving in Europe by the sudden presence of cargo traffic everywhere. At this point your lookout really means something, and we had great fun dodging giant ships and looking on them almost with affection. The first sight of land warmed the cockles of our souls – we’d been at sea well over a month by this point, but as we approached Portugal we received news from colleagues on other boats that things might be more complicated than we were expecting. Hailing what we thought would be a friendly port in Portugal, we were told very sternly to go back where we came from. Didn’t we know this was a state of emergency? All borders were closed. We explained we’d just come from Faial. We couldn’t turn back. Take pity on us, we haven’t walked on land for over a month! They grudgingly let us anchor in a bay with a bunch of other boats, and sent some police over in a small motor boat to tell us we were strictly forbidden from going ashore. This was a huge psychological blow. We were craving fresh food, cigarettes, walking. And we’d seen our colleagues from the other boat posting pictures of the restaurant they had been enjoying the night before. We’d come to the wrong port, clearly.

The boys weren’t to be deterred by these so-called Emergency Laws. After dark they launched the dinghy whilst Laure and I prepared dinner. They came back later with cigars, beers, and tales of land. There was a market, they said. We could go… They hatched a plan for a dawn raid. I was very nervous because the police had been reasonably angry and we had to dinghy right past their launch. We hadn’t even checked in yet and had been expressly forbidden from leaving the boat, even to walk on the beach. We were being Very Naughty Sailors. But the lure of the land was too much. ‘Play it cool,’ I muttered as we very conspicuously tied up the dinghy. ‘Don’t look like tourists’. This was the time when any foreigner was a Bringer of Covid and regarded with great suspicion. I tried to look nonchalant. The French pointed at everything (the beautiful trees, the flowers, the grass) with massive French ‘wow!’s. I staggered about like a newly-birthed foal, unsure any more how to use my legs.

We slinked through the town, seeing Police everywhere and me, for one, terrified about being stopped and questioned. (It seems so silly now, but this was the summer of 2020 atmosphere.) When a uniform would pass, we would busy ourselves looking in a window or actually duck round a corner. Basically looking like cartoon burglars. Once we found the market, we discovered we wouldn’t be allowed in without a mask. So near yet so far! When we’d left Martinique getting a mask was like getting hold of cocaine. We sent Fred on an exploratory mission to a pharmacy while we sat in a café and ordered coffees. I tried to enjoy the experience of European land life. (I was in Portugal having a morning coffee – during Covid times!) But the police were just across the road, and we looked so guilty they kept checking us out. Fred only managed to get us one mask, so Laure had to go finish the job. We hid round the corner across the road, out of the way of the police, waiting for her to come back like teenagers waiting for an older sibling to bring the booze from the offie.

With the mask on, I felt like I was in disguise and relaxed a little. OK, we were still clearly foreigners, but we were blending in with everyone else doing their morning shopping. We went to the market and revelled in the amazing fresh produce on hand. We loaded ourselves up, but we were taking so long… How long before the police boat passed by our catamaran and noticed the dinghy was gone? We were having fun and frolics ashore, but was this going to come back and bite us on the arse as soon as we appeared at the dock? I was the very epitome of highly-strung as I all but dragged my French co-conspirators back to the dinghy. They were so slow. Why couldn’t they see the urgency of the situation? We fired up the outboard and trundled through the port. Where was the police launch? It wasn’t in their spot. Anxiety gnawed at my insides as Fred turned up the throttle and planed us back towards the boat. As we were tying up, I spotted the police boat coming in through the breakwater. Shit! They’d be coming for us for sure!

Don’t worry about putting the groceries away, I insisted, look! (The others, by the way, were still relaxed and laughing, delighted at the escapade.) We had to get out of there. They humoured me and we worked to lift the dinghy and get the engines started. I’m not sure they were particularly moved by my urgency, but I really didn’t want to risk that tender coming over and the authorities asking awkward questions. Surely better just to piss off out of there? We raised the anchor and scarpered, motoring along the coast. Then, since the weather was beautiful and we were in the Algarve, we got out some chilled rosé, prepared some of the tasty new groceries, and had a delightful holiday-mood lunch.

We found the port our friends had ended up in, where the restrictions got magically stricter just as we arrived. But it didn’t matter. We still managed to go ashore, have dinner in the bar with our colleagues, walk around the dusty old town, and visit the weird tall ship anchored nearby, owned by an eccentric pirate type. This was now a waiting game, because the weather at Gibraltar was awful and we were waiting for a window to be able to pass. Eventually we gave up this Portuguese party and followed our colleagues to get closer to the Straits, to be ready for the change in wind. That meant going to Spain, and those bastards really weren’t kidding when it came to ‘go the fuck away, this is a global pandemic you nutcases’. None of the ports would let us in. We had to sneak up to a cliff-edge in a not-really anchorage and piss off some local anglers. We had a party with our colleagues, who had actually made their boat a dry boat for the crossing. We thought about all the wine and rum we’d consumed… The next day we had an illegal trip ashore (still wary of the scary Spanish police) to walk up to the cliff and look out at Morocco. Over there was Africa, for fuckssake.

When the winds finally dropped, we raced our friends through the Straits of Gibraltar and headed for the Balearics to shelter. We were met with a little more friendliness, although the same strict instructions not to go ashore. We went anyway, breaking into a giant old fort, and were thoroughly interrogated by our friendly policeman on our return, who had trusted us. Trusted us. But we were hardened criminals now. It was amazing to be in one of the busiest yachtie tourist destinations in the world and have it practically all to ourselves. It was at this point that we checked the date and realised that our time was almost up to fill in our French tax returns. This became a really big deal and Filou and Laure were almost crying with the frustration (they gave up in the face of the final ‘computer says no’ to filing the return, because their address wasn’t recognised by the system). I was squinting at my mobile, hoping my data would hold out and just guessing random numbers at this point. We had been at sea for almost the whole window the French Administration allowed you for filing your return. By the time we made it to Ajaccio in Corsica, this Transat had taken 44 days (remember my original ride had made it in 23?). We were pretty glad we’d stocked up on too much cheese.

The Douane in Corsica were very excited to see us. A whole squad of them rocked up to the boat. Where had we come from? What the hell were we doing here? Didn’t we know there was a pandemic? But they were so happy. I think we made their day. I think they were bored. This boredom caused a thorough search of the boat for contraband. Any alcohol, tobacco, illegal goods, drugs? Their leader asked. ‘I wish!’ I replied. ‘You can search all you like, we have literally nothing left. If we’d had anything before we left, for sure we would have taken it all before we arrived. It’s been 44 days FFS.’ He gave a ‘you can’t tell me that’ sort of response, and I said I didn’t care, because they could search and search. If they found anything worth confiscating I’d be impressed.

We were very happy to be back safe in Frenchland, to enjoy shore delights and the brief end of confinement that coincided with our arrival. I’d originally planned to stay and play tourist in Corsica, but by this point tensions were beginning to bleed through the cracks in our smiles and a fight was looming. We cleaned the boat and all hastily made our plans to get the hell away from that Lagoon 42. As luck would have it, France had lifted restrictions enough that we were allowed to travel between different parts of the country. So I went to visit Labrador Eyebrows, who was at Maritime College in La Rochelle, before delving into the spooky loneliness of international air travel. I got a camp bed and meal pack in a refugee room at Charles de Gaulle airport, and felt like a VIP in the practically deserted lounges. Then I went to Iceland, who were miraculously letting in travellers from France but not the UK. I had a furry stick shoved aggressively up my nose in one of the first PCR tests, and was released into a Covid-free paradise.

I don’t have space to detail my whole Iceland adventure from that summer. I had promised to go and work on a boat that was going to be doing expedition charters to Greenland from Ísafjörður. Greenland’s borders were shut, but the (French) skipper had persuaded me to come anyway because, why not? I hung out on that boat doing maintenance, having a 20-second-romance with an incredible Spanish adventurer, but most importantly – studying for my Yachtmaster. I met a tough-as-nails (also French) expedition skipper there who gave me the contact of a friend of hers in Cornwall who would be able to take me through the exam. Everything happens for a reason, right? A few months later I found myself on his boat in Falmouth, during the small break that summer in the UK where we were allowed to do stuff, taking my actual bona fide Yachtmaster exam. When the examiner told me solemnly that I’d passed, I didn’t really know how to take it. I mean, I’d worked so hard and done so much to achieve this major thing, and now I had done it. Was I now allowed to call myself a real sailor? I still felt like an imposter. ‘This is a professional qualification’, he reminded me. ‘Internationally recognised. We don’t give them out lightly.’ Surely no-one was going to trust me with responsibility for their boat? What if they all misjudged me? What if I was just an amazingly convincing liar? What if I really don’t know what I’m doing, after all? How many oceans will I have to cross before I’ll believe I actually have some skills, now?

I can’t be a wizard, Hagrid, I’m just Harry!

—- The End —-

PS I got the name for this story from Captain Salsa – who, when he’d mentioned he was about to do a delivery of a boat from somewhere like Thailand to Europe, I’d said oooo take me, take me (it was the pandemic, I was bored). He said ‘nah, you’re seasick and useless’. It’s always hard to tell with him whether he’s joking or not, so I decided not to take it to heart (since I knew I’d grown since we’d last seen each other) – but I did like the ring of the phrase. Seasick and Dangerous, however, sounded way better. Thanks Erik.