‘In 1928 I had my first experience of a hurricane,’ my grandmother Joyce had written in her journal chronicling her life in Antigua. After an eventful summer in Europe, I was rejoining my bateau in Guadeloupe during peak hurricane season. Part of the reason I’d chosen Guadeloupe was that it was the next island from Antigua. I’d given myself a bit of time before I needed to be back in Martinique for work, so had cooked up a plan to get some boat work done and then make my pilgrimage to the land of my ancestors. I was quite excited.

As I explained in the introduction to this project, I’d come to the Caribbean to discover this family I had never known, who had their roots deeply embedded in Antigua. Since my grandfather had also left Glasgow to find work and adventure in the region, and to sail, nothing seemed more appropriate than to sail to Antigua in my own boat. Zen Master had kindly agreed to be part of the voyage, before helping me take the boat back to Martinique. But there were several big obstacles in the way of this dream: my engine difficulties and some pretty hefty weather systems forming on the metaphorical horizon. Welcome to summer 2017 – the year of Irma and Maria.

Before I’d left Annie B in St François for the (European) summer, we’d needed to address the issue of the dodgy engine and what might be causing it. Zen Master had a mechanic friend in the area, so he agreed to come and take a look before I left. He hummed and hawed and made very expensive air sucking through teeth noises. Between them they hypothesised that charming Monsieur M—– had used the wrong oil in the gearbox and that this was going to cost me dearly. I gritted my teeth, because there was nothing I could do, and agreed that the mechanic could tinker with it while I was away. I was hoping the problem wasn’t as serious as they thought – the noises they had made had sounded like thousands.

Fast forward to my arrival in Guadeloupe two months later. I was dirty and tired, having taxied and hitchhiked from the airport because it happened to be a public holiday and there were no buses. I heaved my bags onto the boat, found the key that had been hidden in the cockpit, and was greeted with this sight:

My whole engine was out of its compartment and filling the cabin space. (It turned out that the problem hadn’t been as simple as ‘wrong gearbox oil’.) The interior looked like it had been dismantled and I felt frankly overwhelmed just looking at it. How on earth was I going to get through these repairs? It stank, and was filthy. And all my stuff was everywhere, plus the batteries were flat so no power. I sat in the cockpit wondering what I was going to do with myself, when two people I vaguely recognised pulled up in their dinghy. It was the mechanic and his wife. Zen Master had phoned them and told them to let me onto one of his other boats to sleep. Praise be! A short reprieve from tackling the bomb site. Even though I was knackered and jetlagged, I let them take me out for a drink as they tried to help me come up with plans for what to do next. Suddenly I didn’t feel quite so alone.

The next day, whilst I was wallowing in a pool of overwhelm, Zen Master called asking if I’d seen the weather. Of course I hadn’t. There was a tropical depression coming – a storm due the next day and I should have known about it. As a boat owner I should have been checking the weather every day. I groaned – it felt like there were so many things I needed to learn/do all at once and I couldn’t keep up. From memory, my to-do list looked a bit like this:

- Get the engine out of my living space (preferably by fixing whatever was wrong with it)

- Deal with the batteries and dodgy wiring (where were all these electric shocks coming from all of a sudden?)

- Re-sikaflex the deck fittings and windows so the leaks weren’t so severe

- Strip the mouldy carpet from the interior walls, sand off the glue, and paint a nice clean white

- Why does the toilet smell so bad?

- Why are the stanchions so wobbly?

- If I can’t get the engine back in its hole, how can I mount the outboard to the back of the boat? (Plus associated fibreglass work)

- Mainsail cover/lazy jacks

- New cockpit protection (the French called my current arrangement l’immeuble – a sort of block of flats on 2 levels constructed from building scaffolding)

- Why don’t my solar panels work?

- Anti-fouling and new hull paint job

- New interior lighting solution (why don’t the lights work??)

- Replace various sheets (ropes) necessary for safe sailing

- Dinghy cover

- Fix broken hose

- Re-do the plumbing to my water tank

- Fit new foot pump for the sink (and associated plumbing)

The list went on and was probably longer, with smaller things I’ve thankfully erased from my memory (cleaning mould being a major one). There was a book on boat mechanics in English sitting on my chart table looking at me. I didn’t know where it had come from, or who to thank for it, but I knew I should be giving it some serious attention and not just crying every time I looked at my to do list. The problem was I knew that in theory people learnt to do all these things themselves, and I was always good at things so why not me? The marina itself was a hive of activity, with a clique of piratey young people all alternately snorting cocaine and working on their boats, getting thoroughly ingrained in fibreglass repairs and deck sanding. It was inspiring (apart from the cocaine part, Mum). But I just didn’t know where to start. I found myself helplessly waiting around for Zen Master to come and tell me what to do, and he was evidently running out of patience with me. Little by little I did manage to start whittling down the list. I did simple things like asking the mechanic about my solar panel problem, and going to the shop and buying some new wires and things. This was all I achieved that day apart from laundry, but it was a good start. I did some tidying. Zen Master came and showed me how to do the Sikaflex (a flexible sealant for filling in holes with screws in them), and helped me out with the bits that required two people. I ripped off carpet and choked on fibreglass dust as I prepped my internal walls for painting (all in sweltering airless August heat, with added mosquitoes and a weird plague of moths I wasn’t certain of the origins of). I was overwhelmed but I was learning a lot about DIY, mechanics, and electricity.

It’s only your first boat

In the midst of all this stop-start haphazard work, Zen Master came along with some good advice. I had all these plans: I wanted to put my mark on my new bateau, make her a thing of beauty, paint the hull a nice colour, etc. He brought me back down to Earth. This is only your first boat, he told me. Is it the one you’re going to keep forever? No (in my case, probably just 2 years unless I suddenly decided to cross the Pacific or something, which admittedly was in the back of my mind at this moment). Use your money on these priorities: making her safe, sail well, and a pleasant living space inside. As reality began to creep up on me, I had a serious rethink about my to do list. Boat work takes so much longer than you think it will, especially when you don’t know what you’re doing. The idea that this was only my first boat was liberating. Don’t make her too beautiful, he advised. You want to go sailing and you’re going to make mistakes. Don’t make changes that’ll mean you’re upset when you scratch or damage things. (Also if you’re busy making her beautiful you won’t have time to actually go anywhere.) Don’t get too attached.

He was right, she wasn’t my new girlfriend and I wasn’t going to plan out a long-term relationship with her. I loved my bateau (because if you don’t, everything you do for her seems like total madness) but I knew this could never last. When I first saw her I’d thought ‘this is a boat I could take back to Europe with me’, but after seeing the waves in the Atlantic I’d chickened out of that idea. Later Zen Master told me the provenance of the mechanics book. Someone had given it to him a while ago and he wasn’t sure why since English wasn’t his first language and he already knew most of this stuff. Then when he took responsibility for my boat, he realised the universe had meant it for me. He smiled encouragingly. I was very touched because I really did need a book like this.

Later on I took a break and sat in my cockpit, gazing at the marina, and finding it just so unbelievable that in December I’d opted not to go to a cocaine-fuelled new year party so I could dream about having my own boat. And now here I was back in that very same place and this was my #boatlife.

The best laid plans of mice and men…

The storm came and I sat in my cabin, feeling justified in not tackling any of my to do list and hoping the leaks wouldn’t be too bad. That afternoon Zen Master called and gave me news about our planned departure. I’d still been holding hope for my optimistic timetable for going back to Martinique, although by this time I’d kissed goodbye to the idea of the Antigua pilgrimage. With the engine still in the middle of the cabin and no repair solution in sight (the mechanic had told me that to investigate the problem properly, we were going to have to do an expensive haul-out), just getting home before term started was the top priority. Anyway what with the weather, Zen Master now didn’t think we’d be able to leave until the end of the month. It gave me more time to work on the to-do list, but he kept making ‘if we can’t go at all’ noises, which niggled at the back of my mind.

Then the mechanic announced that he was going away on holiday, which was a really big blow to my timetable. This is when we started considering fixing the outboard to the back of the boat so we could do the trip without the engine, but Zen Master was still concerned about the windless area passing Dominica. And I didn’t have the fibreglass skills to attach the mount I’d bought. The mechanic would be passing by Martinique on the 15th October (and not back in Gwada until much later), and so I started making crazy plans for doing the haul-out there. All my plans at this point were desperate compromises and my spirits were sinking lower and lower. The Martinique haul-out idea proved unfeasibly expensive, so I was looking at a much longer than anticipated sojourn in Guadeloupe. The thought of having the engine in my cabin all that time made me break down. Until this point I’d seen it as a temporary inconvenience and hadn’t really been living in my space, but now I realised I had to see it as a permanent fixture for the foreseeable future. I needed to do my life, despite it.

The biggest blow of all came at the start of September, with a major hurricane forecast: hurricane Irma. A guy from the Capitainerie came round to make sure I had an idea of what I was doing to secure the boat and to advise in general. He didn’t seem too anxious about things so I wasn’t so worried, but then he didn’t have a boat. All he said was to make sure I was on land chez someone when it hit. At that time the path was predicted to come right by Guadeloupe, and all signs were saying it was going to be nasty. All plans for leaving were put on hold as the marina busied itself for hurricane preparation.

One of the young pirates invited me for a dinghy ride out into the lagoon later that day. I brought rum and some pre-prepared lime and sugar for ti punch. We paddled about and everything seemed so calm, so blue and so full of fish and coral. A hurricane just didn’t seem possible. Nothing seemed real. His friends turned up for a spot of dinghy-jousting with oars and the rum quickly became rhum salée thanks to the sea water. They informed me of how hurricanes were done around here. You take everything off the boat possible, secure it, gather your valuables, and go to someone’s house with raclette. Then you eat raclette and get wasted so your hangover is too horrible the next day to go and see the damage. You just don’t think about it. Then, when everyone’s ready, you all go together and cry at your shattered dreams.

Later, as weather reports worsened, he and his friend informed me that this was basically the apocalypse. I should kiss goodbye to my boat. They were both a bit teary. For my part, I couldn’t react because there was nothing I could do at that moment. But they interpreted it as ‘doudou, you really don’t understand the gravity of the situation’. So they reiterated and the pirate cried to himself a little about how much he loved his boat, and showed me pictures of the destruction from last time a strong hurricane had hit Guadeloupe full on. It wasn’t pretty and none of the boats had survived.

Let go of the things you can’t control

This first hurricane season with the bateau was a traumatic eye-opener. With my engine camped out in the middle of my living space, the mechanic who put it there away on a long holiday, and two major storms on their way (because Irma was just the start – next to come was Maria), life felt very much out of my control. I found myself regularly in tears – with the frustration of it all, and the loneliness of not really having any friends (except Zen Master whose time I was loathe to monopolise), especially people I could speak my native language with. At this point when I spoke in French, it still required other people to make a lot of effort with me in order to understand, and I was socially awkward. Despite living 7 months in Martinique, it was really these couple of months in Guadeloupe that turned me into a confident French speaker. It was excruciating but for the sake of my sanity and loneliness I had to persist. At that time I was regularly on the edge of despair, and took up smoking because I found that rolling a cigarette and enjoying it in the cockpit to get away from the disaster down below was the one thing in my life I could control. Right now it’s still my go-to solution for hurricanes and other big disasters (like global pandemics – looking at you, COVID-19). I’m hoping soon I’ll be able to teach myself to resort to making tea to solve my mental crises, but I’m always drawn to the rebellious option.

I wasn’t together in the head enough at that time to learn the lesson I should have done – but it all came down to control. I was stressed out because my mind was trying to get a grip on something I couldn’t possibly influence. It wanted to be in control of my life and where things were going, but of course that’s futile. I’m a natural planner and I had a solid timeline for how I thought things were going to play out. I was going to go to Antigua, and when that fell through, at least I was going to get my repairs done and be home in Martinique before work started. But you can’t control the weather, or whether your mechanic is available to free you of your motor. You have to chill and let it go. Accept your total powerlessness in the situation. It’s the only way to free yourself from the cycle of mental anguish. Sometimes it’s good not to plan too much. Also, being a newbie boat owner, especially when you’re doing it alone, is tough. There’s a lot to learn all at once, and a helluvalotta responsibility. The only way to deal with it is in bite-sized chunks. I desperately needed other people to help and I was lucky to have Zen Master, but I should have been more pro-active about doing things for myself because other people have their own lives. They don’t want to be there constantly bailing out a helpless depressed child. Or that’s how I saw myself anyway. It was a tough time and by the coming of the hurricane it definitely wasn’t over, but by God did I learn things.

In 1928 I had my first experience of a hurricane! By now we had moved to Scotshill which had been my grandparents’ house. The house had 29 rooms, 9 verandas. There were 86 windows and doors to bar. The windows were sash windows, with shutters outside, which had to be closed every night, with a bar on the inside to keep out burglars. When a hurricane warning came we had to bar & nail these shutters on the outside as well.

The warning came in the evening, the barring was done, the chickens were caught and put in a cellar. Nothing happened during the night.

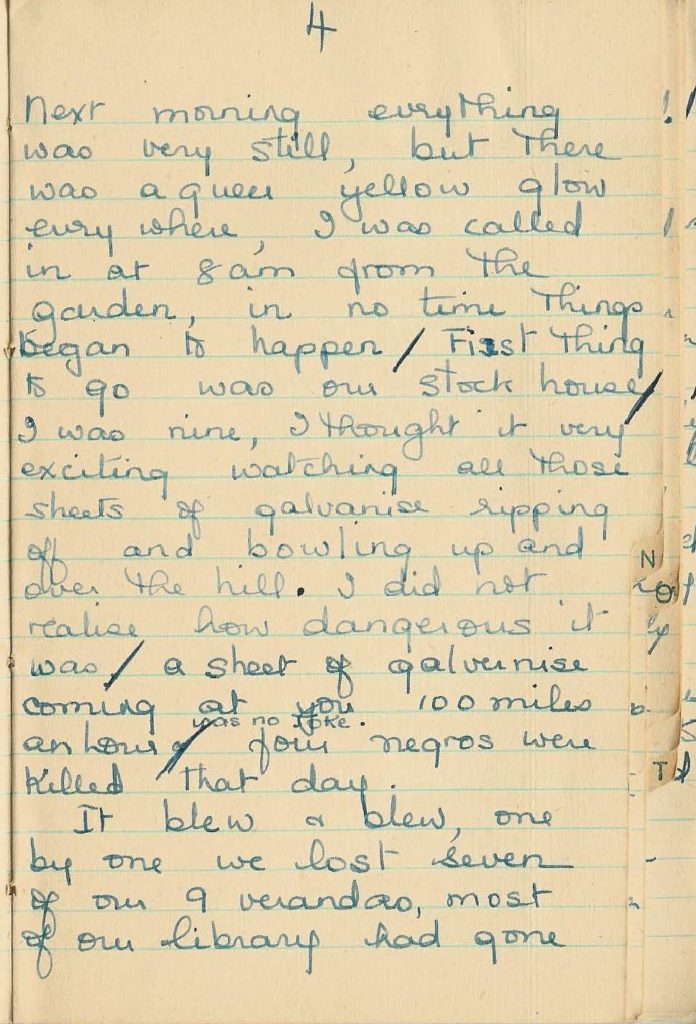

Next morning everything was very still, but there was a queer yellow glow everywhere. I was called in at 8am from the garden, in no time things began to happen. First thing to go was our stock house. I was nine, I thought it very exciting watching all those sheets of galvanise ripping off and bowling up and over the hill. I did not realise how dangerous it was, a sheet of galvanise coming at you 100 miles an hour was no joke. Four negros were killed that day.

It blew & blew, one by one we lost seven of our 9 verandas, most of our library had gone and a pantry. A big room with 10 windows was shifted 15 feet into the garden, when the door in the room below burst inwards. Our garage collapsed on our car.

At 10pm that night we were all huddled round an open trap door in the middle of the nursery floor. Thank goodness the hurricane subsided before we had to go down into that dreadful cellar. It was floored with boulders, the home of cockroaches, centipedes and tarantulas, which always come in during bad weather.

3 weeks after the hurricane we had an earthquake, it lasted 15 minutes. The noise was terrifying. I was lying on my bed with a book. It felt as though something enormous hit the side of the bed. Then everything shook and rattled, but there was no serious damage. Only a few cracks here & there. Joyce Robertson (née Nugent) ‘Some of My Travels’

Right now I find myself in a very similar situation – some very cool summer plans relying on a tight time schedule which have now been thrown into disarray by a global situation outside of my control. Thanks to the pandemic it’s impossible to plan – all we can do is sit back, try and remain mentally sane, and watch what happens next. We have to accept the things that we can’t control or we’re lost. Bonne courage à tous!

Glad to hear you abstained from the cocaine!!

This is riveting reading.